Tags

Ameeta, Dev Anand, Film City, Guru Dutt, Johnny Walker, Kaagaz Ke Phool, Kamini Kadam, Maratha Mandir, Nanda, Navrang, Niranjan Sharma, Prabhu Dayal, Prof KPR Nair, Radha Krishan, Rajendra Kumar, Sandhya, Sujit Kumar, Tumsa Nahin Dekha, Tun Tun, V Shantaram, Waheeda Rehman

Had it not been for my autograph book, I wouldn’t remember the dates of our first visit to the magical city. October 1959. I was 13 and my brother 10 when father decided to take mom and us for a holiday to the celebrated capital city of film stars. Siblings at 7 and 4 were found too small to register anything and were left behind in the care of grandmother.

Now, Bombay was not Bombay if it wasn’t far. But how far is far? “We’ll start at 7 in the morning,” said my father reading from his much used copy of the railway time table, “and continue the whole day, sleep the night in the train, get up in the morning, then continue the whole of that day until it was night, sleep that second night again in the running train and reach Bombay in the morning.” The idea of sleeping in the train had left Davinder and I open-mouthed and wide-eyed. Years later we discovered that my father had decided to take the slowest train to gain us—and him—that night travel experience twice over.

The night before our journey, two peons (along with a couple of inspectors) were dispatched to the Old Delhi Railway Station, one to buy tickets from the counter as soon as it opened and the other to occupy window seats while the train was still in the yard. Counting one berth as equivalent of four seats, my father had thought that a sleeper berth would cost four times the normal fare and dismissed the idea as horrendously wasteful. My mother too had woken up early that day to cook a mountain of food for our entire feed on the way. Even here, my father had the inside story: On winter nights waiters spat on the plates and wiped them clean rather than put their hands in cold water. So home food is any day cleaner. Davinder and I resignedly understood that it was also cheaper.

Finally as day broke for the second time in a very tired train, we were in a new world. The landscape was wet and lush green and the railway stations, named this or that Road, were sparse and clean. Darkish locals wore turbans and caps and life seemed contented and peaceful. After a long tunnel (when to my great relief I remember that lights were turned on in the train) stations began to come quicker and more crowded. Women wore flowers, girls skirts and heels—Anglo-Indians, we understood from films (or “Englaundians!” as my favourite uncle would call them)—and men wore jackets and hats like Johnny Walker. Blunt-nosed local trains appeared, either zipping past or running parallel on the next track so we could see inside them. Sometimes they overtook us, sometimes we did. My father pointed to the arched bows on top of them, which he explained went drawing electricity from the cables running overhead. I was surprised they made such racket; electric trains I had thought were silent.

But no mistaking, we were in Bombay.

From a large sprawling station—must have been Victoria Terminus—we took a taxi for Khar. (It took us the whole visit to get used to such odd names for localities: Dadar, Ghatkopar, Bori Bundar, even one called Chinchpokli.) Khar is where we were staying with a friend of my father’s. But it wasn’t like sharing beds with them as we were used to with relatives. We had a room to ourselves with an attached latrine-bathroom. Every morning the servant brought us a sumptuous breakfast of tea and toast-sandwiches (with plentiful ketchup) after which we set out on our own on full-loaded stomachs, today to this place, tomorrow to that. Every morning my father’s friend dropped in—as always, they were extra courteous to my father, his friends; they were particularly admiring of his being honest and teetotaller, in spite of being an Excise Officer of Delhi—and suggested places to go. We never met his family and were happier for that. It would be a shame having to bridge the mismatch between them so rich and generous and us so utterly uncouth and miserly.

My impression of the Bombay of those days is of clean, washed surroundings and overcast, drizzly skies; of general orderliness with an air of civility. And custard apples, which we saw hanging from every other bush. Our own bungalow had them and next morning they came with breakfast! We discovered the fruit together as a family; sweeter than sugar! And the Parsis. My father’s friend informed him, and he us, that it’s a small community in which everybody is rich. You wouldn’t find them anywhere except in Bombay, they don’t marry outside their community and if somebody begins to slide, the rest of them pull him up. After this Davinder and I decided whatever statues we saw in marble, in fancy headgear and well done were of Parsis. I don’t think there were too many of Shivaji’s statues in Bombay in those days. My mother, however, got stuck (and remained stuck) over the way local women wore saris. “Look at them, splitting buttocks! Shameless!” she said of the strand pulled between the legs and tucked in at the back. Today I wonder what she would say about men wearing lungis if we had gone further down to Madras. All of them Ravan-like dark, all with moustaches curling inwards over the lips and their gesture of folding up those white lungis as though getting ready for a street fight! It was for reasons such as these I think that Bombay remained the farthest we went as a family even though Madras would have given us an extra night in the train and Trivendrum even perhaps a fourth.

We took a red double-decker bus right on the first day—they tended to be rather new and well maintained, those buses—and climbed to occupy seats closest to the front. Surprisingly not everybody preferred to sit on the upper deck. Next day we took the local train, rattle and all, and started with marvelling at the way people waited on the platform without creating a ruckus. Also its horn as it approached sounded classy, closer as it was to cars than the shriek of steam engines. They gathered speed quicker and weren’t too crowded. I was particularly struck by their overhead rotating fans that looked like a gyroscope. Did the fan power the gyroscope or gyroscope the fan, I kept wondering, looking at the dancing fans. Some of the places we visited were Chowpatty (not so much for its famous chaat but the sea front which was a new experience, even for father), Tarapore Aquarium, with strange kind of fishes slithering behind glass panels (what if somebody threw a stone at the glass, Davinder and I secretly wondered, rather hoped, in fact wished; then saw the guard!), Gateway of India and Taj, with a row of horse drawn phaetons parked in front (in Delhi we had seen only Rashtrapati using an elaborate one on 26th January), Hanging Gardens (where nothing was hanging but shootings took place—we recognised a high point overseeing a curve of the ocean) and the lonesome Pali Hill (where film stars lived!). Davinder tells me we also took a boat ride to Elephanta caves but I have no memory of that.

During our visit hoardings of V Shantaram’s Navrang and Guru Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool dominated the cityscape. Navrang shouted from the housetops that it was in colour and showed Sandhya carrying a dozen or so pitchers on the head that jutted out of the main board, while Kaagaz Ke Phool sought to cast its magic in emphatic, brooding black and white. Guru Dutt’s close up wearing his familiar wrinkles over the forehead and a twisted smile underneath occupied 3/4th of the space but it was Waheeda Rehman’s tall, slim (and may I whisper sexy) figure that received 3/4th of popular attention—it certainly did mine. Both were art films according to my father’s friend, both expensive to make and both failures at the box office. Still we could hardly leave Bombay without seeing a film and after some discussion settled for a pricey brand new theatre called Maratha Mandir, Pride of Maharashtra. Taking our host’s advice, we had actually gone to experience the theatre’s rare genuine Cinemascope projection and Guru Dutt’s masterpiece came as a bonus. I couldn’t understand the fuss about that wall-to-wall stretch of the screen.

It was towards the end of our stay that we got to hit the great studio trail. This was going to be the peak of our entire visit and that’s for when we had got our autograph books!

I don’t remember the specific studios that we visited but they fell in two categories: lively, compact, city bound ones within easy distances of each other and a larger but dead one in a jungle outside Bombay, which was a newly started government facility called Film City. Stars resented having to go such great distances and therefore the City wasn’t picking up, our host told my father and he us. At each studio that we got to visit, we showed the security guards a letter from my father’s friend, then waited among 20-25 others on the side until called out and given a pass to enter. During the wait, all eyes were fixed on the entering or exiting cars, everybody hoping to catch a glimpse of a passing star. Once Davinder pretended (even later insisted) he saw one but he was bullshitting as usual. He had done the same at Pali Hill. Nobody had passed there or here and we didn’t see anybody.

Inside the premises people went about their business as though they took film stars for breakfast. No one seemed enamoured of them. What luck to be working in films, we thought. Another thing common to all studios was the sight of red-faced men and women walking about or sitting in groups. Make up, Davinder and I exchanged silent notes. And extras, waiting outside the shooting floor on call, we deduced. But why were they wearing orange clothes? I was proud to crack this ‘technical’ issue on my own, which even Filmfare had been silent on: This had to be for reasons of black and white photography where white may register as too bright as it did in newsreels. 10 years later I got the fact confirmed in a discreet aside with the genial Prof KPR Nair of cinematography after one of his early classes with us in the Film Institute.

Finally while entering a shooting floor through a cut out gate, we recognised an old moustachioed man sitting alone. Davinder and I returned and walked past him again. Niranjan Sharma, told a studio hand. “Yes, he is a character actor,” he confirmed. Somewhat dismayed, both of us agreed that Mr Sharma was friendlier on the screen than sitting cold like that. But we still queued up to take his autograph. He filled up a whole page without looking at us even once. Our first autograph!

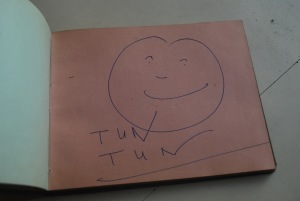

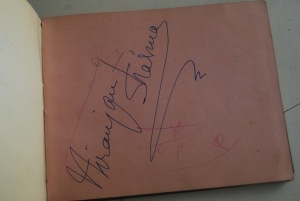

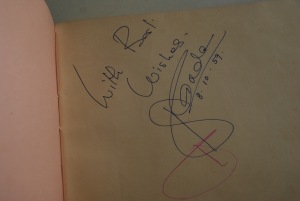

Others that we collected over the next few days were Rajendra Kumar, Nanda (turning those days from Baby to Kumari), a certain Prabhu Dayal (he used to play second lead as a well-meaning rejected lover, a latter day Sujit Kumar of sorts), Kamini Kadam (more a Marathi actress than Hindi), the cute but a mere 4-footer Ameeta (Tumsa Nahin Dekha, arched eyebrows and all)…. and of course the 2-ton Tun Tun! Fatso Tun Tun was a real delight: She just drew a large circle on our pages and wrote her name in two halves, those were her autographs! When the books came to us and we smiled, she responded with her trademark finger-between-teeth girlie giggle. We had to give it to her; Tun Tun was the same, on screen as well as off it. Our day was made.

One actor that we missed seeing by a whisker was Dev Anand. Somebody thought he was shooting on one of the floors and directed us there but it turned out that he had just left. I however remember the incident for entirely different reasons. For the first time I became aware of the difference between how studio hands in Bombay referred to their stars and we the louts from Delhi did. While for us he was Devanand does this, Devanand does that, the Bombay workers referred to him in genuine respect as Dev Saheb. Twice or thrice that afternoon I got a bloody nose on that account before the fact sank in my head. Nobody ever used that expression in north India. Much, much later I understood that both sides were after all speaking from two different worlds. The production staff knew the man as a senior professional, while we had nothing else to go by but the characters he played on the screen.

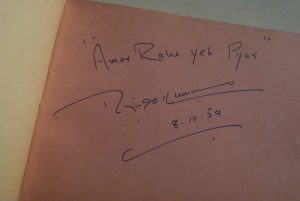

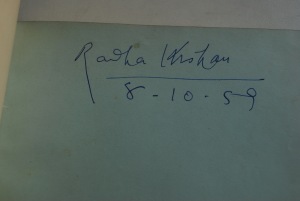

Rajendra Kumar and Nanda, on the day we entered their studio floor through another cut out gate, were shooting for a film called Amar Rahe Ye Pyaar. Except the stars, the atmosphere on the set was no different from how it was years later when we shot our dialogue films in the Film Institute. They were sitting on folding chairs, a fan turned in their direction, as lighting was going on on a basic set with a large studio camera—Mitchell NC or BNC, I now know—presiding. We saw no hangers on, nobody fussing over the two of them. Nanda sat rather demure and bashful as Rajendra Kumar, a mischievous smiling playing on his lips, was whispering something to her. Was he being vulgar? Poor Nanda, my sympathies instantly went gushing for her. We recognised two others on the same set and waylaid them. Prabhu Dayal, who besides playing a role was also directing this film and comedian Radha Krishan who was for the first time trying his luck as producer with this film. Two years later when we went to watch the film in Delhi, we were surprised to see it open with Radha Krishan’s garlanded portrait. The man had died of a heart attack during its making.

Piecing together details of my father’s conduct over that Bombay visit I am tempted to believe that he somehow wanted me sucked into films. He had little faith in my abilities but unknown to me he did think I was good looking and kept nudging me to ‘straighten up’ and not be shy when approaching film stars.

“Don’t just shove that book to them but also smartly stay on and talk,” he said. “That’s how you get roles in films.”

I was horrified at the thought. “But what if I am selected?” I barely managed to blurt out.

“Just look at him,” father addressed my mother in disbelief. “As if they are all waiting for him!” Then he turned to me, “If you are selected, stay on! What else?”

“No-o-o!” The idea was horrendous to me. We had come on a holiday and there was no way I was going to be left behind!

Not for the first time, my father wrote me off with disgust.

But certainly films fascinated me on my own. There was a grace about that curtain parting and revealing the white rectangle. (Was it manual or somebody pressing a button? And if it was the button, was it done twice, starting and finishing, or just once?) I loved that beam of light coming from behind and filling the screen. (Was it the porthole that allowed just the right rectangle of light through, blocking out the rest?) Some invitation cards that my father received had the same proportions and similar rounded corners and I used their blank side to endlessly fantasise about the magical film screen.

Later when I came by a magnifying glass, I found it had much more to offer than just burning paper. If correctly held in front of the wall, it could form an upside down image of what was in front of it. Which was unraveling the secret of the still camera. Came the definition of persistence of vision and I could understand how ingeniously the principle had been used both in a movie camera as well as the projector. My spine tingled when I learnt of the early practice of a camera being used for shooting, processing and also projecting films.

What however took me a long, long time to grasp was the cut. In many ways the question was framed during this Bombay visit but it remained unanswered until 10 years later when I joined the Film Institute of India.

The one scene that we stayed on to watch was with Niranjan Sharma, now back to being cheerful and kindly, sitting at a the head of a dining table as family members sat around eating. A chirpy little girl said something and everybody laughed. A young girl then got up excusing herself to go to college and left.

The actors kept speaking their lines on their own as the lighting kept being switched on and off to somebody’s command. The camera also was wheeled in a number of times into the action. (How I wished I could be allowed to take just a peep through ‘his majesty’!) And this went on for such a long time that even Davinder and I felt thoroughly bored and were happy to walk away. Was one or the other actor muffing lines, expressions? Were they stuck with faulty equipment? Was it a particularly difficult scene?

I went to see the film when it came to Delhi. The dining table scene came and went just as they had been doing it. So what had been all that big fuss about? The answer came to me years later when I joined the FTII. That’s when I discovered the cut—first the cut itself and then over the years its technical and aesthetic dimensions.

In a way, language of cinema is all about and around the cut. Watching shooting in Bombay I had assumed that the cut is a function of the film camera. That that expensive gadget automatically chooses details of the scene which are likely to be missed out in a wider view. It was a major disappointment to learn that a film camera is nothing but a ‘mindless’ recording machine. It is just a still camera with a sewing machine kind of mechanism attached; which pulls the film, holds it in place while a frame is exposed and pulls it again for the next frame, all very quickly.

So how is the cut then made? My eyes remained wide open when we were told in the editing class that a cut is a physical splice made between two strips of film, two separate shots. Camera doesn’t make them, the editor does. First using a pair of scissors (!), then scraping one end with a shaving blade (!!), then applying watery ‘cement’ from a used nail polish bottle (!!!), and finally bringing the two ends quickly together in a cast iron splicer! Just how crude can you get?

I could not sleep that night; my mind kept going over a faint twitch that a misaligned splicer might cause as the cut went in front of the projection gate.

Good fun going through it.

Thanks.

I must complement to a 13 yrs old boy’s memory about the Dream City! Fabulous write up! Your articles always persuade the reader to step in to the life of each character you write about! I presume that your father’s wish to see you in the film faculty has come true!

Thank you Kusumji. Indeed my father was happier to see me on a job than face uncertainties of an active filmmaking career.

Bombay seems to have been a better place than Mumbai ! Thoroughly enjoyed the travel back in time, Amazing how vivid your memory is even after 56 years. And thanks for mentioning Radhakrishan and Ameeta. They were two of my favourites and its years since I heard them mentioned. But Tuntun takes the cake. She must have been a very nice person.

Tun Tun was indeed a gem. I don’t remember where we met Ameeta. Bombay was certainly better. There was distinction between I, II and III class compartments of the Local which was clearly visible. Often times you saw a I class going empty as the III next to it was crowded. I don’t think any body was left behind on the platform for reasons of crowding. Thanks Pankaj.